Welcome to Part 3 of the Mind-Body Series! In Part I of the series, we addressed the role of the limbic system and the HPA-axis in mind-body medicine and overall health. In Part 2 of the series, we addressed the role of the vagus nerve and the social nervous system in mind-body medicine and overall health.

This week I will be discussing the roles of the vagus nerve, the enteric nervous system, and the gut microbiome in emotional, mental, and physical health. Let’s start with a brief review of the vagus nerve…

As stated in Part 2, the vagus nerve is a part of the autonomic nervous system, which controls the involuntary function of our internal organs during times of stress and rest. It is particularly important during the parasympathetic nervous response, which allows the body to rest, digest food, and store energy.

The vagus nerve connects the brain to major organs, including the heart, the lungs, and the digestive tract (i.e. esophagus, stomach, pancreas, gallbladder, and intestines). It also communicates directly with the gut through the enteric nervous system, which regulates gastrointestinal balance. We will discuss the enteric nervous system in just a second.

What is the Gut-Brain Axis?

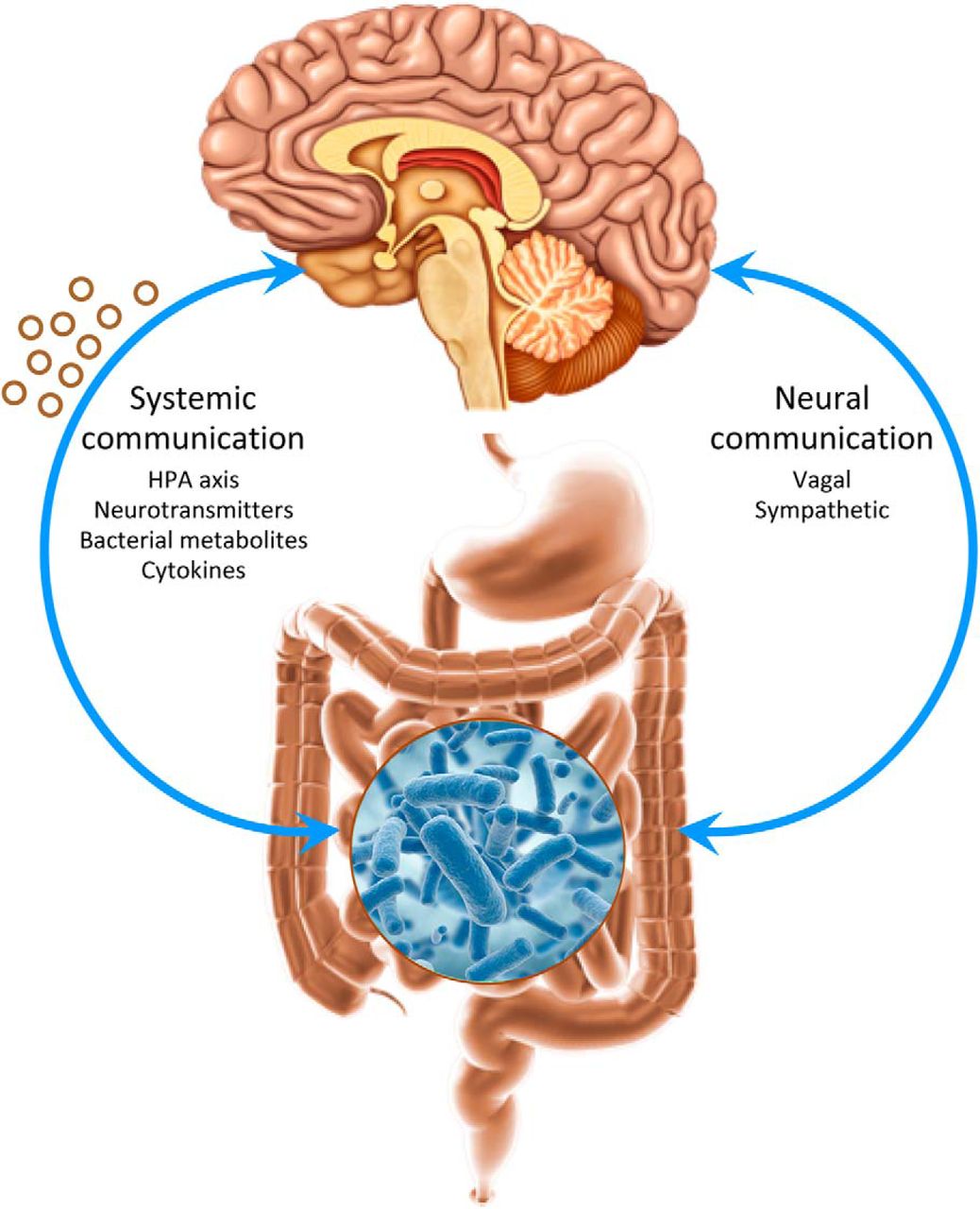

The Gut-Brain Axis refers to the bi-directional communication between the GI tract and the brain through a complex system that includes the vagus nerve, sympathetic spinal nerves, the enteric nervous system, hormones, neurotransmitters, immune proteins, and gut microbes. It exists to maintain balance within the GI tract and to connect the emotional and cognitive areas of the brain with digestive functions.

What is the enteric nervous system?

The enteric nervous system is the digestive system’s own independent, local nervous system that is embedded within the wall of the entire digestive tract, from the esophagus to the anus. The enteric nervous system contains 500 million neurons. (Compared to the brain that contains 100 billion neurons.) Along with gut microbes, it produces more than 30 neurotransmitters that can cross the blood-brain barrier and have an effect on cognitive and emotional health. Due to this extensive network, the enteric nervous system is referred to as the body’s “second brain”.

This “second brain” contains three types of neurons:

- sensory neurons, which receive information from sensory receptors within walls of GI tract (i.e. heat receptors, stretch receptors, chemical receptors, etc.)

- motor neurons, which control GI motility and secretion

- interneurons, which relay information from sensory neurons to motor neurons

Some well-known neurotransmitters produced within this complex include:

- Acetylcholine, which is an important component in parasympathetic response. It stimulates smooth muscle contractions, sphincter relaxation, intestinal secretions, hormone release, and blood vessel dilation.

- Dopamine, which helps regulate movement, attention, learning, and emotional responses. It plays a major role in the brain’s reward system. As a part of that system, it enables us to not only feel pleasure and satisfaction, but to also take action to move towards it. This neurotransmitter plays a very important part in addiction.

- GABA (Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid), which is an inhibitory neurotransmitter. As such, it decreases brain activity, producing a calming effect as a result. This helps to control feelings of anxiety, stress, and fear. [Random Fact: Did you know that GABA is naturally found in fermented foods? Like microbes in our gut, the beneficial bacteria in fermented foods have the ability to produce neurochemicals that can directly impact our brain and nervous system. We’ll discuss this more in a bit.]

- Melatonin, which regulates our circadian rhythms and sleep patterns. It is also produced in the brain’s pineal gland.

- Norepinephrine, which activates the sympathetic physiological response and opposes the actions of acetylcholine. It restricts sphincter relaxation, constricts blood vessels, and reduces smooth muscle contractions, intestinal secretions, and hormone release.

- Serotonin, which activates feelings of well-being and happiness, increases gut motility, regulates appetite, and stimulates blood vessel constriction to assist in blood clotting during the wound healing process. 95% of ALL serotonin is produced in the gut!

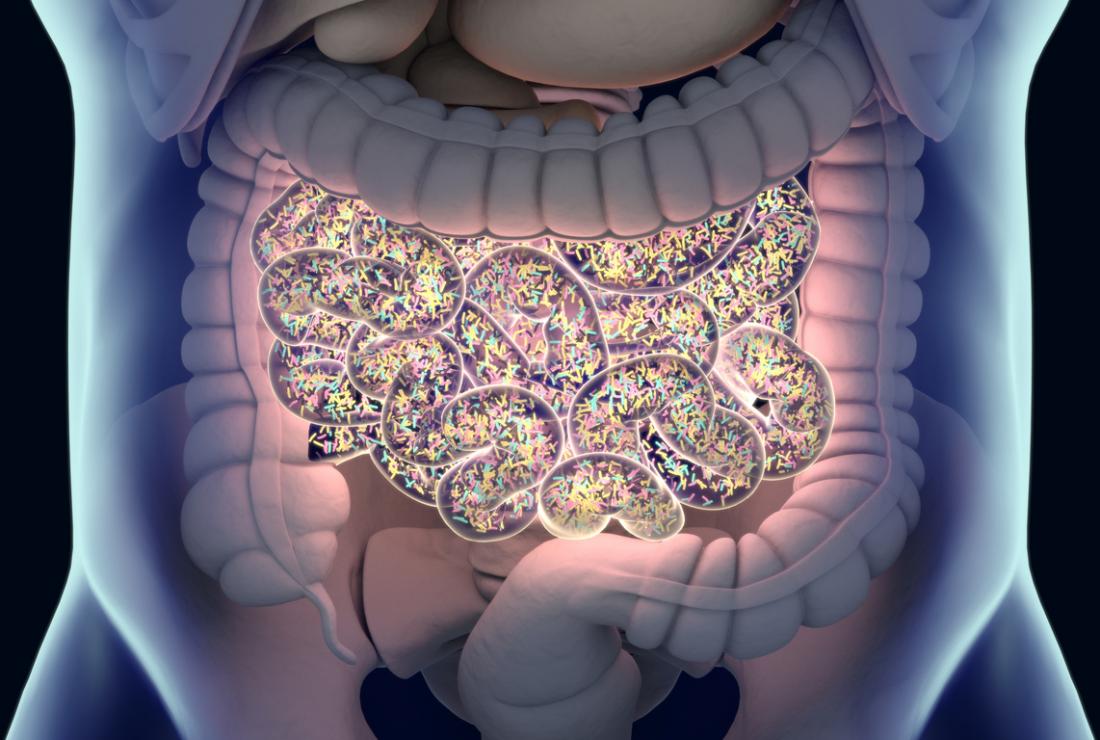

What is the Gut Microbiome?

Humans have ALOT more bacterial cells than human cells. They live on our skin, in our nose and ears, and most of all, in our gut. The gut microbiome includes commensal, or “good”, bacteria, as well as, some species of fungi that are non-invasive. They do not penetrate the barrier provided by the digestive tract, and therefore, do not trigger a local or systemic inflammatory response.

They produce short-chain fatty acids which help to control appetite and maintain the blood-brain barrier along the spinal cord and around the brain. They produce essential amino acids, minerals, and vitamins for basic cell function. They increase nutrient availability and absorption by enhancing digestion. They assist in the elimination of toxins. And lastly, as stated above, they even produce neurotransmitters, such as, Acetylcholine, Dopamine, GABA, Melatonin, Norepinephrine, and Serotonin.

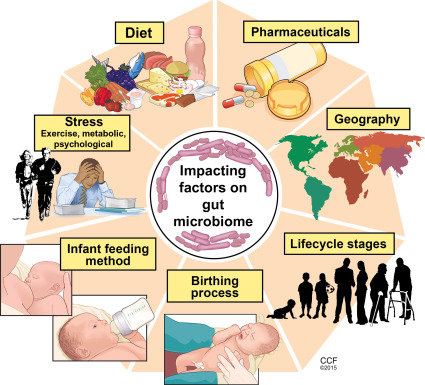

Just as gut bacteria affect the brain, the mind and the brain can also exert a profound influence on the microbiome. Numerous studies, for example, have shown that chronic psychological and emotional stress suppresses beneficial bacteria and promotes the overgrowth of harmful bacteria, increasing one’s risk for infection and causing more gut inflammation.

Stress-induced changes to the microbiome then affect brain and behavior as bacteria release inflammatory proteins as a defense mechanism. The inflammation then causes a disruption in brain chemistry, making one more vulnerable to anxiety and depression. This process may explain why more than half of people with chronic GI disorders, such as, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and IBS are also plagued by anxiety and/or depression.

What role does the gut microbiome have in early brain development?

At birth, an infant’s gut is sterile. The following first three years of life are critical for brain development and for the maturation of the gut microbiome. As previously mentioned, the microbiome provides many essential nutrients and neurotransmitters necessary for brain development and overall wellness. Research has shown that disruption of the microbiome’s maturation process during any of the neurodevelopmental phases may have detrimental effects on mental health because the generation of new nerve cells is regulated by the gut microbiome. Some research also suggests that the gut microbiome is crucial in building a healthy and resilient stress response during early childhood development. If a child’s stress response is underdeveloped, he or she will have less ability to cope with difficult situations and bounce back from them quickly. Thus, he or she will have an increased risk for anxiety, depression, insomnia, high blood pressure, a weakened immune system, chronic indigestion, GERD, and heart disease.

What role does the gut microbiome have in optimal brain function during adulthood?

The gut microbiome continues to play an important role throughout our life. According to research, the gut microbiome undergoes significant changes once we reach old age, with some beneficial species, such as bifidobacteria, decreasing in numbers along with an overall reduction in microbial diversity. That shift within the microbial environment is linked with low-grade, chronic inflammation and increased gut permeability. These changes in the gut microbiome along with higher levels of inflammation are not good for our brain. As a matter of fact, they have been linked to an increased risk of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease.

How does the gut microbiome affect sleep?

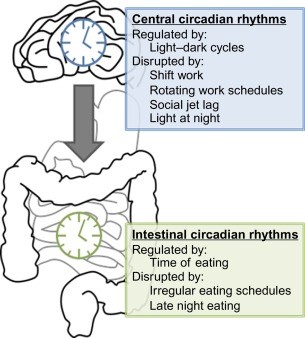

Our gut microbiome has its own daily rhythms that work in synergy with our own sleep and wake cycles. The daily rhythms of our microbiome is tightly linked to our dietary patterns and frequency and timing of meals, which impact its diversity and metabolic activity. To add, our microbiome produces it’s own melatonin.

When travelling to different time zones, working late-night shifts, or suffering from lack of sleep, we not only disrupt our circadian rhythms, but also those of our gut microbes. And since gut microbes respond to when we eat, irregular eating patterns can also disturb them. When these rhythms are imbalanced, microbial diversity is compromised, with higher levels of microbial species that are associated with inflammation and an increased risk of intestinal permeability (aka leaky gut). Disruption within the gut microbiome equilibrium is known as “gut dysbiosis” and can be resolved by getting adequate sleep, incorporating therapeutic fasting, establishing regular eating patterns, and embracing a healthier diet with a focus on increasing fermented foods, or probiotics.

Surprise! Your GI tract is also an immune organ!

Your digestive tract is THE defining line between your body and the external world. This means it encounters more threats from outside invaders than any other part of the body. It forms a barrier against the penetration of food, chemicals, microbes, and more. Defects within that barrier can contribute to the development and perpetuation of inflammatory bowel disease, multiple allergies and intolerances, autoimmunity, and more. Therefore, a large portion of your immune system lies within the gut, particularly in the intestines as small masses of lymphatic tissue. This extension of your immune system is called Gut-Associated Lymphoid Tissue, or GALT. It monitors intestinal bacteria populations and prevents the growth of pathogenic bacteria and other microbes in the intestines.

Which disorders have been linked to the Gut-Brain Axis?

Anxiety, depression, autism spectrum disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, insomnia, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, IBS, IBD, Celiac’s disease, other autoimmune diseases, peptic ulcer disease, multiple allergies and intolerances, and obesity have all been linked to a disruption along the gut-brain axis.

So, how do you heal the gut-brain axis?

I integrate traditional African healing ways with Naturopathic medicine to help restore the health of your digestive system and your brain while simultaneously supporting your well-being on all levels.

Healing the Gut-Brain Axis from a Traditional African-Centered Perspective:

Traditional healing within the African diaspora includes the use of fasting and bitter herbs/foods to help optimize digestion and detoxify and heal the gut. Gut-healing herbs, known as demulcents and vulneraries in western herbalism, are also used to help heal a damaged gut. By improving digestion, detoxifying the gut, reducing gut inflammation, and healing the lining of digestive tract, we help to cleanse the mind, the emotions, and the spirit simultaneously.

Aside from therapeutic fasting and herbal treatments, the regular consumption of fermented foods in the African diet benefits gut, mental, and emotional health in the long-term. Foods that are commonly fermented include:

- grains, such as, sorghum, maize, rice, and millet (commonly eaten in the Yoruba and Fulani diets as gruels and fermented drinks)

- beans (commonly eaten in the Yoruba diet as fermented locust beans)

- milk (commonly eaten in the Fulani diet as yogurt and fermented drinks)

- root vegetables (commonly eaten in the Yoruba diet as fermented cassava, or known in a variety of preparations, such as, “gari”, “fufu”, “lafun”, and “elubo”)

- other fruits and vegetables (commonly eaten in Southern African-American cuisine in various forms, such as, “chow chow”, pickled beets, pickled okra, pickled peaches, and more)

- and even herbs (commonly eaten in the Malagasy diet as fermented ginger beer)

Healing the Gut-Brain Axis from a Naturopathic Perspective:

- Therapeutic fasting to give the gut a chance to rest and heal

- Foods and herbs that support the liver and gallbladder to optimize digestion.

- Demulcent herbs to reduce gut inflammation and heal inflamed areas within the gut

- Vulnerary herbs to heal damaged walls that line the digestive tract

- Fermented foods and/or probiotics to support a healthy microbiome

- Various mindfulness exercises to tone the vagus nerve (i.e. deep breathing exercises, meditation, alternate nostril breathing, and heart rate variability biofeedback)

- Craniosacral therapy to stimulate the vagus nerve through light touch

My services will be available beginning this October at The Center: A Place of Hope in Washington, which is an in-patient treatment facility for trauma, various mental illnesses, eating disorders, and addictions. For more information about the services I will be offering, or how to arrange accommodations at The Center, you may contact me through my website’s Contact Page (click here).

Be sure to like and follow my facebook page and/or my instagram page to stay updated for next week’s Part 4 of the Mind-Body Series, “The Green Mind Theory”, where I will be discussing how nature and social environments influence our body, our mood, our behavior, our emotions, and our spirit.

Until next time,

Dr. Richmond

Remaining Posts of the 5-Part Mind-Body Series:

- The Green Mind Theory (Next Week)

- The Neurobiology of Spirituality

References: